Trust is all you need: Inside the PKI that powers Plug & Charge

A deep dive into the digital identity system and public key infrastructure that underpins the cybersecurity of the EV charging ecosystem.

The previous article peeled back the curtain on the cryptographic engine room behind Plug & Charge: the digital keys, signatures, and encrypted conversations that make an EV simply plug in and start charging. We explored how an EV and a charging station can trust each other instantly, how data stays confidential, and why public key cryptography is the backbone of every secure interaction you experience – whether through a charging cable or through the browser you’re using to read this article.

This week, we shift from how messages are protected to how identities are proven.

Because behind every Plug & Charge session lies a sophisticated public key infrastructure (PKI), a system of digital certificates and trust anchors that ensures every actor in the ecosystem is exactly who they claim to be.

Think of PKI as the backbone of trust: issuing digital “passports”, validating identities, and ensuring that an EV doesn’t just connect to a charger, but to a trusted one. Without this “chain of trust”, Plug & Charge simply wouldn’t work. And as EV charging infrastructure grows into a critical part of our energy and mobility infrastructure, it’s becoming an increasingly attractive target for attackers. This is why it’s essential that cybersecurity is designed in from day one, not patched on later as an afterthought.

In this article, we’ll explore:

How a digital certificate actually looks like

How the chain-of-trust principle works, from a root CA down to leaf certificates

The different digital certificates that make the Plug & Charge ecosystem function

Where each certificate must live – in the EV, in the charger, or in the backend

At the end of the day, a digital certificate is nothing more than a high-security ID card – one that expires, can be revoked, and must be maintained. And understanding how that system works is the key to understanding how Plug & Charge truly stays secure.

Once you understand these basic principles, it’ll be a walk in the park to follow next week’s article where we’ll explore the complete lifecycle of a Plug & Charge session.

Let’s get to it.

Basic principles: a PKI’s chain of trust

In a PKI system, a trusted third party known as a certificate authority (CA) issues digital certificates that contain public keys and identifying information about the certificate holder, such as an EV or a charging station.

Let’s take the charging station as an example.

A charger first generates a digital key pair: a private key (kept securely inside the charger) and a matching public key. The charger then uses that public key, along with its identifying details, to create a Certificate Signing Request (CSR), which it signs with its newly created private key and sends to a certificate authority – using the charge point operator’s backend, or CPMS. The CA verifies the request and, if valid, issues a signed certificate that binds the charger’s identity to its public key, allowing the charging station to authenticate securely towards an EV during Plug & Charge sessions.

Anyone who wants to verify that authenticity of a digital certificate simply checks the CA’s digital signature using the CA’s public key, which is stored in the CA’s own certificate. This creates what’s known as a chain of trust: a tree-like structure that starts with an end-entity or “leaf” certificate (such as the one held by an EV or charger) and ultimately leads back to a root CA certificate, the final trust anchor. Computer scientists love this analogy – a root at the top, leaves at the bottom – because it perfectly captures how trust flows downward through the system.

In the EV charging world, this trust chain spans multiple players who all depend on one another to make Plug & Charge work smoothly:

The electric vehicle (EV)

The EV manufacturer (OEM)

The charging station

The charge point operator (CPO)

The mobility service provider (MSP)

The certificate provisioning service (CPS)

The operators of the V2G Root CA

And the operators of the various data pools and cloud services required for certificate provisioning

If you want to read more about the purpose of all these roles in the wider e-mobility ecosystem, then I highly recommend the article Plug & Charge: The technology, the ecosystem, and the road ahead of seamless charging.

A coordinated effort between all these stakeholders, across different industries and regions, is essential to delivering a truly seamless and secure charging experience – no matter which MSP or location a driver chooses to charge their EV.

How does a digital certificate look like?

Alright, so we know there’s a certificate authority that has the power to create a digital certificate, and that digital “passport” carries a public key and the CA’s digital signature, among other pieces of information.

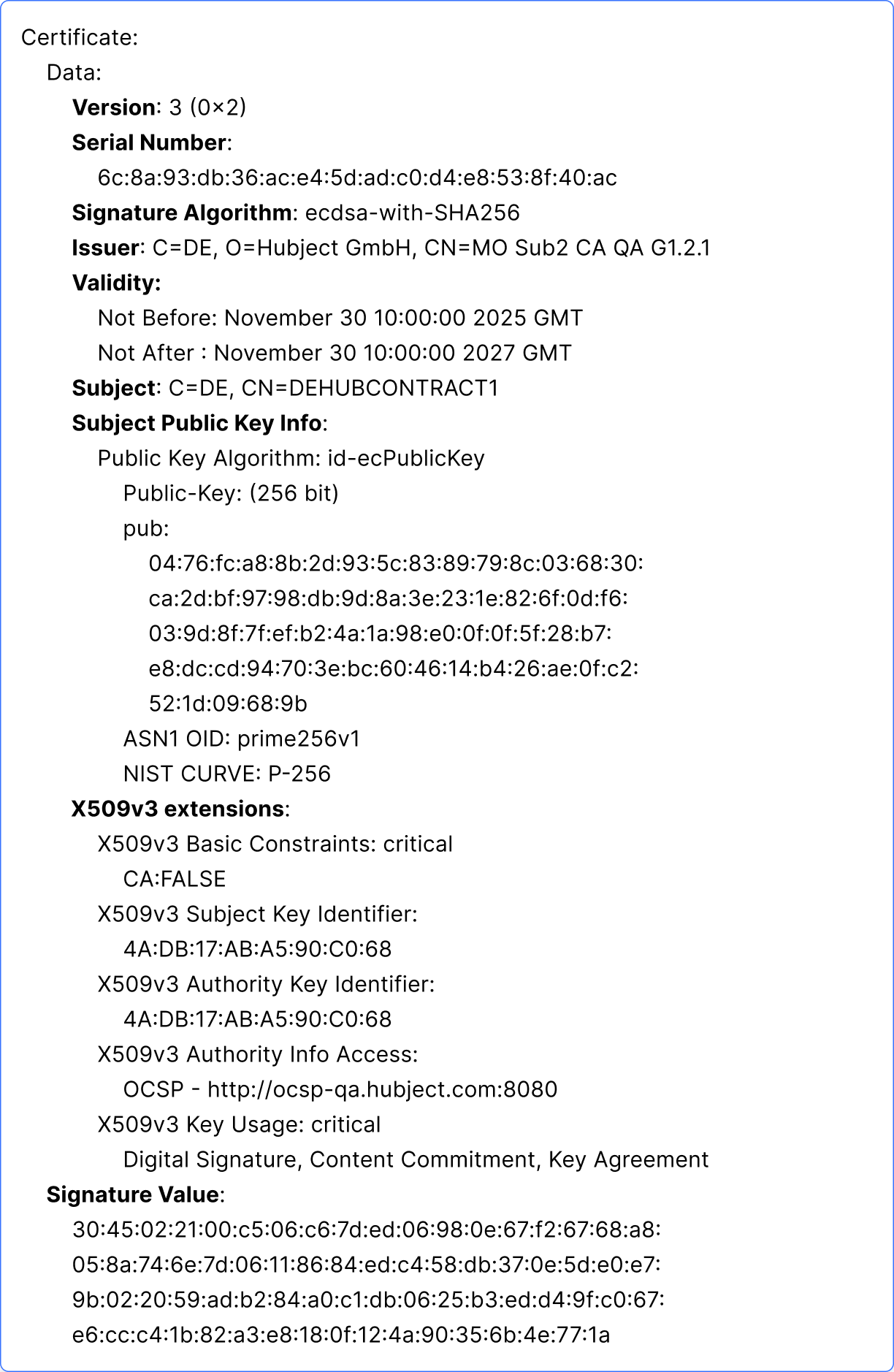

Let’s have a look at an example. In particular, let’s examine a contract certificate, the one the EV uses to identify and authorise itself at the charger to receive energy.

Let’s analyse this certificate step-by-step:

Version: This indicates we’re looking at a standard X.509 version 3 certificate, the foundation of modern PKIs and transport layer security (TLS).

Serial Number: A unique identifier issued by the certificate authority for tracking and revocation.

Signature Algorithm: This certificate is signed using ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) with SHA-256 hashing. Check out the previous article in case you need a quick refresher on digital signatures and hashes.

Issuer: This tells us who issued the certificate. Hubject GmbH is the operator (‘O’ = Organisation), based in Germany (‘C’ = Country), who issued this certificate. The CN (Common Name) ‘MO Sub2 CA QA G1.2.1’ is the name of the certificate authority operated by Hubject that issued and digitally signed this contract certificate.

Validity: This certificate starts to be valid on November 30, 2025 at 10 am and expires exactly 2 years later.

Subject: This is the leaf certificate (lowest end of the chain of trust), representing the e-mobility account ID (EMAID) DEHUBCONTRACT1, which is the identifier of the MSP’s billing account – the contract number to which all charged energy will be billed.

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: This public key uses ECDSA and was created with the elliptic curve (‘ec’) NIST P-256 (aka secp256r1 or prime256v1, as mentioned in the previous article), which is the mandatory curve for ISO 15118-2.

Public Key: The long hex blob represents the public key. It’s what the charger uses to verify signatures created by the EV with its matching private key, which the EV securely stored when the contract certificate was installed. Elliptic curve public keys are represented as 04 (indicates an uncompressed key) followed by X and Y coordinates of the point on the elliptic curve.

Extensions:

Basic constraints (critical): ‘CA=False’ means that this certificate cannot act as a certificate authority (CA) and, therefore, not issue any child certificates (because it’s already a leaf certificate at the bottom end of the chain of trust). The critical flag means clients must process this extension, or reject the certificate.

Subject Key Identifier (SKI): A hash-like identifier for the CA’s public key. Used to link certificate chains efficiently.

Authority Key Identifier: Similar to an SKI

Authority Info Access: This is where you can contact the OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol) responder to check the revocation status of this certificate. We’ll cover OCSP further down in this article.

Key Usage (critical): Specifies what cryptographic operations the public key contained in the certificate is allowed to perform. This public key can verify digital signatures, prove the sender’s identity, and securely establish shared session keys.

Signature Value: This is the ECDSA signature over the certificate body.

In ISO 15118-2, each X.509 certificate is capped at 800 bytes, with its exact contents defined by what’s known as a certificate profile – basically a recipe for what goes inside. I won’t drag you down that rabbit hole just yet, but it’s worth knowing that this is how every (Plug & Charge) certificate gets its structure and purpose.

Step by step: the chain of trust from leaf to trust anchor

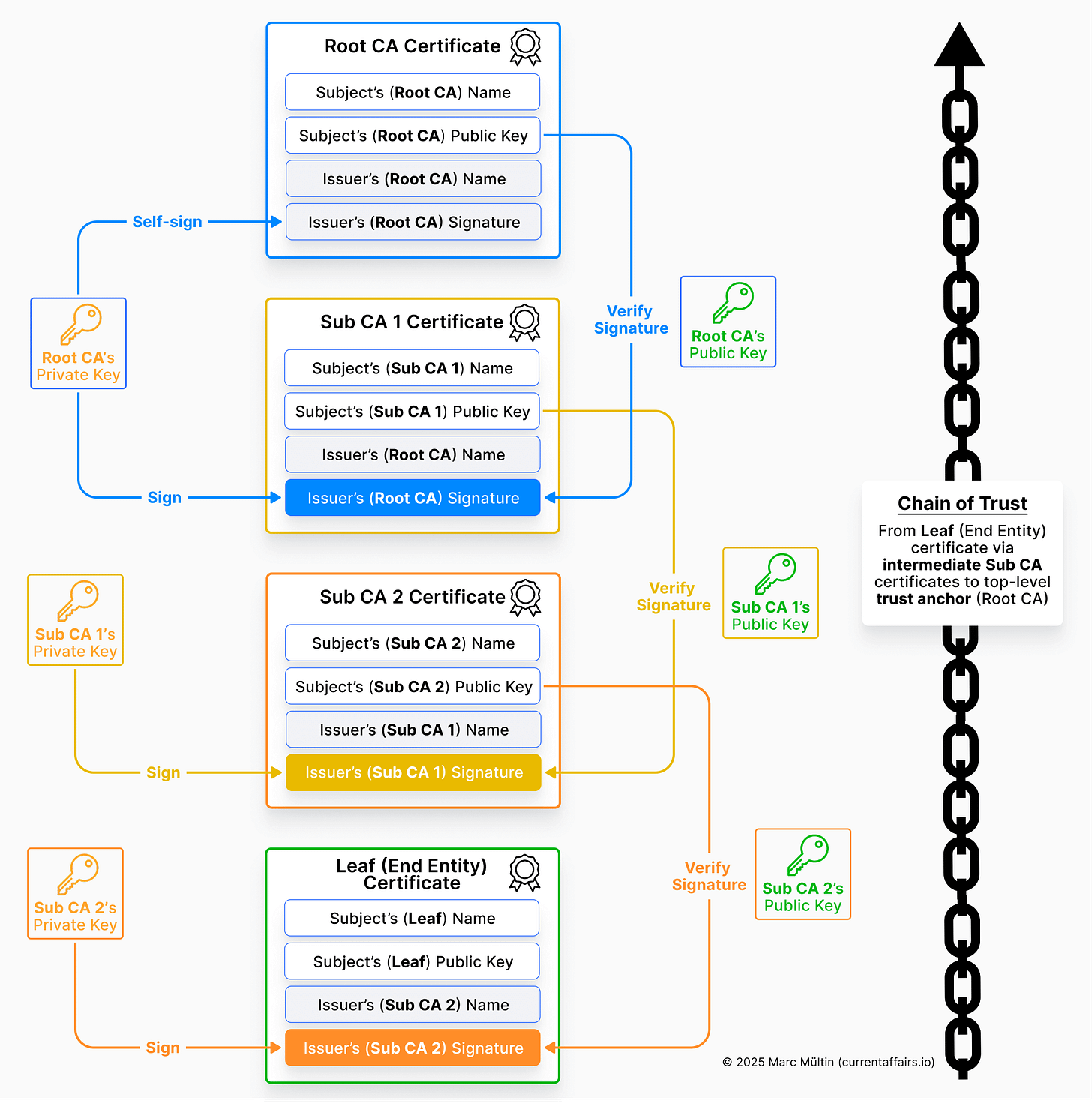

OK, now that we know more about the content of a digital certificate, we can make sense of how the “chain of trust” principle in a PKI actually works, meaning: how trust flows from a Root Certificate Authority (Root CA) down to an end-entity or “leaf” certificate through one or more intermediate (Sub CA = Subordinate Certificate Authority) certificates.

The diagram below captures the hierarchical flow. Let’s go through it step by step to make sure it really clicks.

Root CA Certificate (trust anchor)

The Root CA is the highest authority in the hierarchy which every participant in this PKI ecosystem needs to trust. It self-signs its own certificate, meaning its issuer and subject are the same. Its public key is trusted implicitly (pre-installed in browsers, operating systems, or EVs and chargers). It uses its private key to sign subordinate (Sub CA) certificates.Sub CA 1 Certificate (first intermediate CA)

The Root CA uses its private key to sign the certificate of Sub CA 1. Sub CA 1’s certificate contains:

Its own name and public key (subject fields)

The Root CA’s name as the issuer

A digital signature created using the Root CA’s private key

Anyone who has access to the Root CA’s certificate can verify this signature using that Root CA certificate’s public key, confirming that Sub CA 1 was legitimately issued by the Root CA.

Sub CA 2 Certificate (second intermediate CA – optional)

Where a PKI uses more than one Sub CA: The Sub CA 1 now acts as an issuer for Sub CA 2. Sub CA 1 uses its private key to sign Sub CA 2’s certificate. Verification of Sub CA 2’s certificate uses Sub CA 1’s public key. This adds another layer in the trust chain but still maintains verifiable continuity back to the Root CA.

Leaf (end entity) Certificate (the final link)

Sub CA 2 uses its private key to sign the Leaf Certificate, which includes its own public key and identifies the end entity. In the world of Plug & Charge, this belongs to and identifies a vehicle, charger, or mobility service provider. Verification of the leaf certificate is performed using Sub CA 2’s public key.

Chain of trust verification

When, for example, an EV receives the leaf certificate alongside the corresponding Sub CA certificates of a charging station during a TLS handshake:

It verifies the leaf’s signature using Sub CA 2’s public key.

It then verifies Sub CA 2’s signature using Sub CA 1’s public key.

Finally, it verifies Sub CA 1’s signature using the (already pre-installed) Root CA’s public key.

Because the Root CA is trusted a priori, the entire chain is trusted, thereby verifying the authenticity of the charging station it’s connected to.

Trust flows downward: the Root CA grants trust to Sub CAs by signing them.

Verification flows upward: the client (e.g. EV or charging station) verifies each certificate’s signature using the public key of the issuer above it, until it reaches the trusted Root CA (the “trust anchor”).

Remember: this is standard PKI practice, not specific to ISO 15118. You can check this out yourself: just click the little icon next to the website address in your browser’s address bar to open the certificate viewer.

In Chrome, a popup appears. Click “Connection is secure”, then “Certificate is valid”. You’ll see two tabs:

General, which summarises this website’s certificate

Details, which reveals the full certificate hierarchy

In this case, GTS Root R4 is the Root CA, WE1 is the Sub CA, and currentaffairs.io is the leaf certificate.

If you expand the fields, you’ll notice they use elliptic curve cryptography (ECDSA) for digital signatures and SHA-256 as the hashing algorithm – the same modern cryptographic standards used in Plug & Charge.

Why we are using Sub CAs in a PKI

In a PKI, subordinate certificate authorities (Sub CAs) act as a buffer between the all-powerful Root CA and the everyday certificates used in the field. The Root CA’s private key is the ultimate trust anchor. If it were ever compromised, the entire ecosystem could collapse. That’s why it’s kept offline and used only rarely to sign Sub CA certificates. These Sub CAs then handle the operational work of issuing certificates for vehicles, charging stations, or mobility service providers (MSPs). This setup lets the Root CA remain untouched and protected, while any compromised Sub CA can simply be revoked without bringing the whole system down.

In ISO 15118 Plug & Charge, this hierarchy is taken one step further. The Root CA (the V2G Root CA) signs a first-level Sub CA, often operated by a global trust provider like Hubject or Irdeto, which then signs second-level Sub CAs for regional or organisational entities – say, a national MSP, a car manufacturer, or a charge point operator. This two-tier model balances security, governance, and scalability: it allows the ecosystem to expand internationally while maintaining clear lines of control and trust. Think of it as a carefully pruned tree: the Root stays safe underground, while each branch (Sub CA) can grow, operate, or, if necessary, be cut off without harming the entire organism.

The ISO 15118 PKI ecosystem

Alright, if that all made sense so far, then you’re ready for an overview of the ISO 15118-specific public key infrastructure.

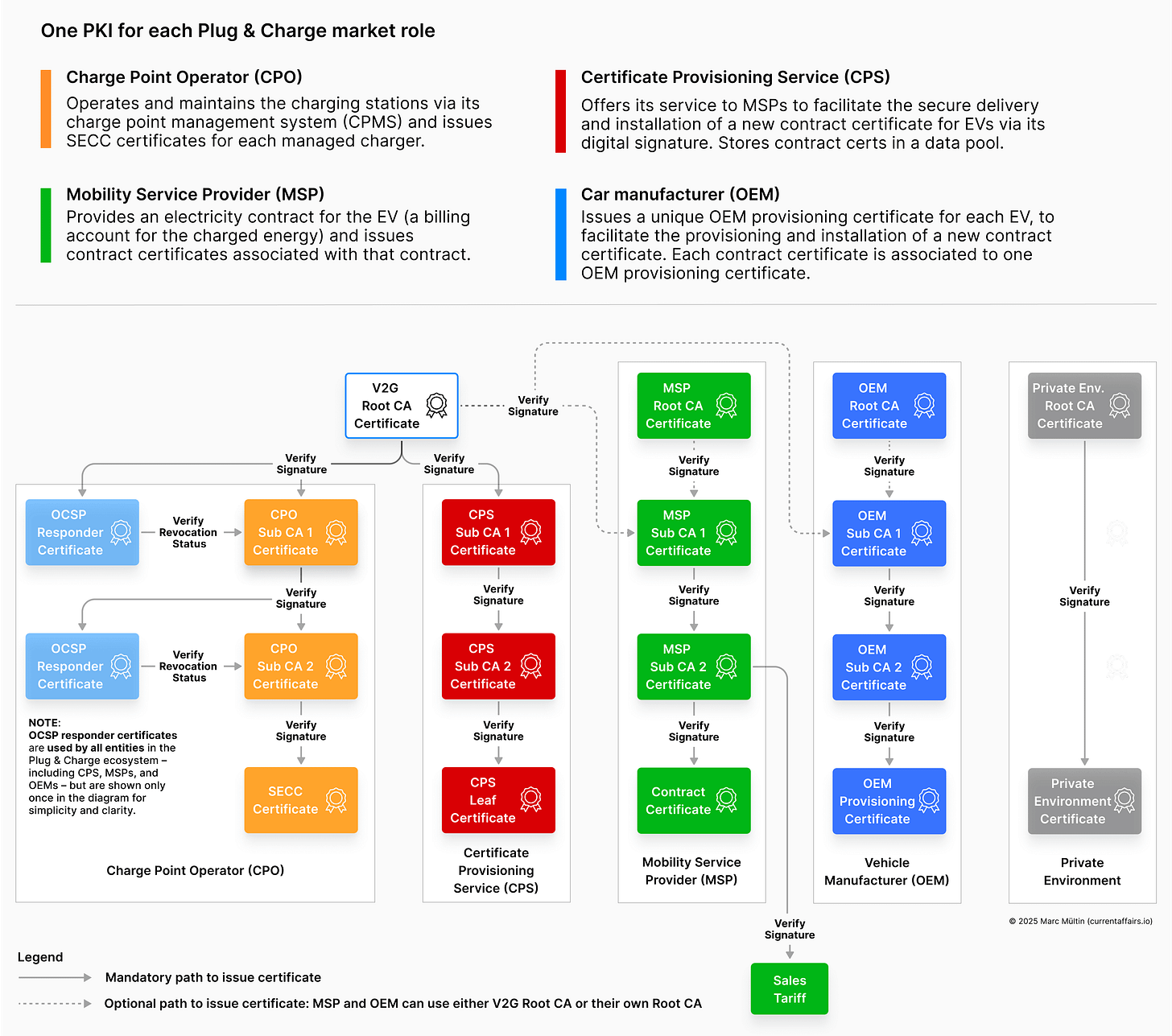

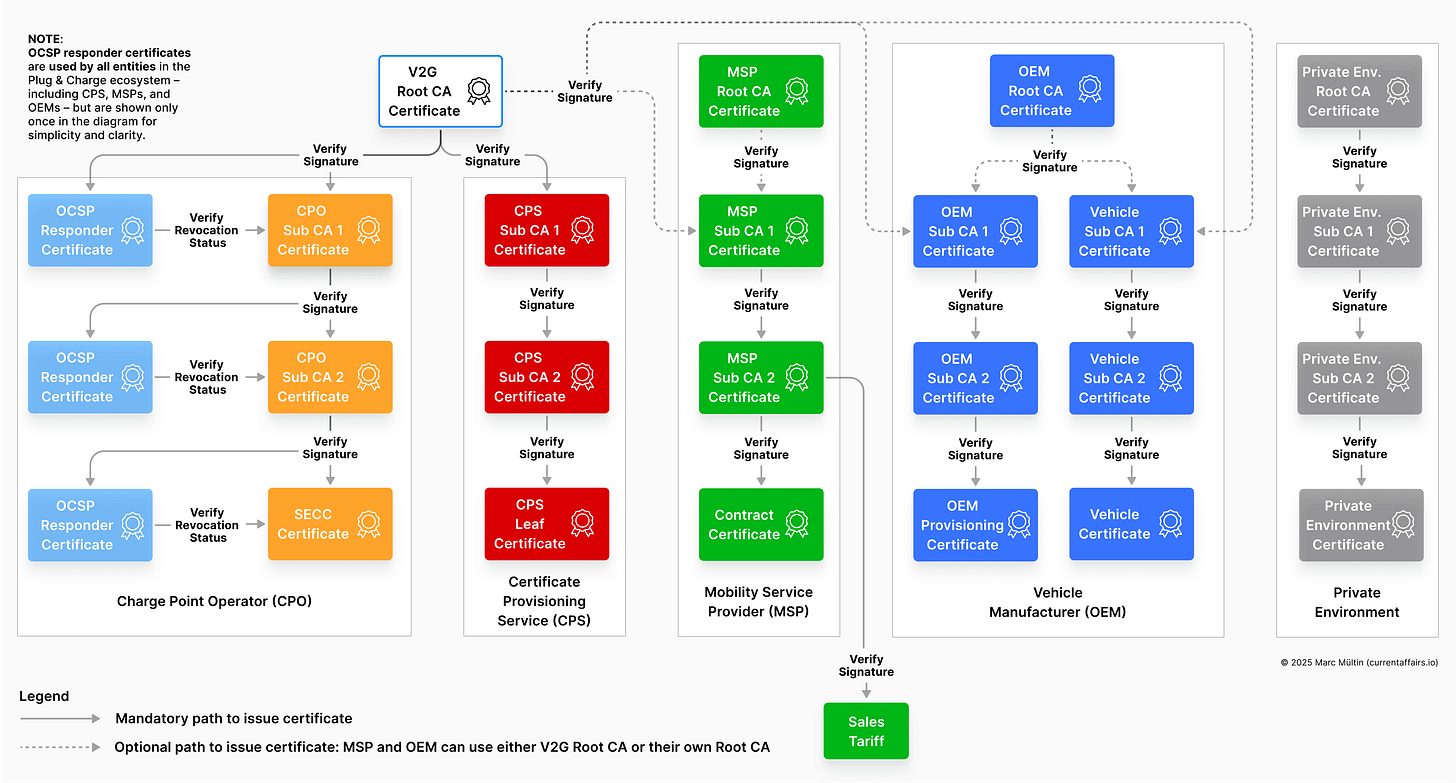

The illustration below summarises the Plug & Charge PKI specifically defined in ISO 15118-2, showing how trust and certificate management work across all market roles. We’ll also briefly cover the difference to an ISO 15118-20 PKI, but let’s first unpack this one step by step in plain language.

The common root of trust

At the center is the V2G Root CA Certificate. This is the trust anchor for the entire Plug & Charge ecosystem. Every other certificate – whether for a CPO, CPS, MSP, or OEM – is ultimately signed (directly or indirectly via intermediate Sub CAs) by this Root CA.

The charge point operator (CPO) and certificate provisioning service (CPS) are required to use the V2G Root CA as their trust anchor when issuing their Sub CA 1 certificates.

In contrast, car manufacturers (OEMs) and mobility service providers (MSPs) have the flexibility to either rely on the common V2G Root CA or operate their own root CA to issue and sign their Sub CA certificates, depending on their security, compliance, and operational needs.

Running your own root CA is costly and complex. It requires secure infrastructure, dedicated experts, strict procedures, and carries high risk if mismanaged – which is why most MSPs prefer to rely on the shared V2G Root CA instead.

Car manufacturers, on the other hand, often operate their own root CA to maintain full control over vehicle identities, meet strict security and compliance requirements, and protect their brand and customers from external trust dependencies.

A walk through the role-specific PKIs and leaf certificates

Each major market actor has its own PKI branch, with one or more Sub CAs under the Root CA.

Charge Point Operator (CPO)

The CPO manages chargers and issues an SECC certificate for each charging station. SECC stands for Supply Equipment Communication Controller and is ISO 15118 speak for the communication device that sits inside the charger and manages the secure, digital communication with the EV.

The charger sends the SECC certificate alongside the Sub CA certificates to the EV during a TLS handshake to identify itself and establish a trusted and confidential communication channel. The EV verifies the authenticity of the CPO Sub CAs using the V2G Root CA certificate that was pre-installed – either during manufacturing or before vehicle delivery to the customer – ensuring that the charging network it connects to is legitimate and trusted.

Certificate Provisioning Service (CPS)

When ISO 15118-2 was published in 2014, the authors couldn’t predict how many MSPs would choose to operate their own Root CAs instead of relying on the shared V2G Root CA. If every EV had to store and manage the Root CA certificates of potentially dozens or even hundreds of MSPs, memory and update management would quickly become impractical – especially given the high cost and strict optimisation requirements in automotive electronics.

To solve this, the Certificate Provisioning Service was introduced as a trusted intermediary, always operating under the V2G Root CA (originally expected to exist in only a handful instances worldwide). The CPS verifies a contract certificate issued by an MSP, re-signs it with its own private key, and stores it in a data pool called Contract Certificate Pool (more on that in next week’s article) from where it can be sent to the EV – establishing transitive trust: if the EV trusts the CPS (via the pre-installed V2G Root CA) and the CPS trusts the MSP, then the EV can safely trust the MSP’s contract certificate without needing to store every MSP’s Root CA.

Thanks to the CPS’s digital signature, the EV can verify that the contract certificate and its encrypted private key are authentic. This is done using the CPS Leaf Certificate, which – together with the CPS Sub CA certificates – is included in the signed contract certificate bundle the EV receives to install the contract certificate and the associated private key securely. That private key can only be decrypted by the EV itself, using the Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) key agreement protocol – which we briefly discussed in the previous article – and the OEM Provisioning Certificate’s public key.

Once installed, the EV presents its contract certificate during a Plug & Charge session to the charger and uses the corresponding private key to generate digital signatures.

The charger verifies these signatures using the public key contained in the contract certificate, confirming the EV’s authenticity and authorisation for charging.

Mobility Service Provider (MSP)

The MSP provides the EV’s billing contract and issues the Contract Certificate tied to that contract. As mentioned before, it uses the service of the CPS to help the EV verify the authenticity of the contract certificate and to eventually store what is called a signed contract certificate bundle to a data pool called Contract Certificate Pool. That data pool is managed by the PKI ecosystem provider, such as Hubject, Irdeto or Gireve. A car manufacturer subscribes to this data pool to get notified of newly created contract certificates that were provisioned specifically for one of their EVs.

Vehicle Manufacturer (OEM)

In ISO 15118 terminology, the vehicle manufacturer is referred to as the OEM.

The OEM issues an OEM Provisioning Certificate for every Plug & Charge-capable vehicle, serving as the identity of the EV.

Each EV has at least one such certificate, while vehicles that support multi-contract handling – allowing multiple contract certificates from various MSPs to be stored – may have a corresponding number of provisioning certificates to manage those separate contracts securely.

This OEM provisioning certificate allows the vehicle to securely request and install (i.e. provision) a new contract certificate from the Contract Certificate Pool – either via the OEM’s secure over-the-air (OTA) update link, or via a charging station. Although ISO 15118 offers a dedicated mechanism to install these contract certificates, it appears that car manufacturers prefer their own OTA communication link to safely store them in their EVs.

Private Environment

A private environment refers to a physically controlled charging setting, such as a private fleet depot or a restricted-access car park.

This concept was introduced to offer a simpler, more cost-effective Plug & Charge setup for non-public charging scenarios. I won’t dive deeper into it here, as it’s unclear whether this concept has ever been implemented in practice. However, if your company has, please reach out. I’d be glad to update this article and explore how it works in reality, along with its advantages and drawbacks.

If that sounded like a mouthful, I feel you. But don’t worry – in the upcoming finale of this Plug & Charge series, we’ll break it all down step by step: how a contract certificate actually finds its way into your EV, and how a full Plug & Charge session unfolds from start to finish. I’ll also include a clear, visual walkthrough that ties everything together and makes the whole process click.

Checking a certificate’s revocation status with OCSP

You probably have noticed the OCSP Responder certificates on the left in the illustration above and asked yourself: what’s that?

Let me explain.

OCSP, short for Online Certificate Status Protocol, is a way for systems to check in real time whether a digital certificate is still trustworthy (i.e. has not been revoked). For example, a certificate might be revoked if its private key was compromised, the organisation’s details or ownership changed, or the device was retired.

In the past, the old method was to download long Certificate Revocation Lists (CRLs), files published by the CA that contained every certificate that had been revoked. OCSP made this process much faster: instead of downloading and parsing an entire list, a device simply asks the CA’s OCSP responder about one specific certificate and gets a quick “good,” “revoked,” or “unknown” reply.

To make this possible, the certificate authority issues a dedicated OCSP responder certificate to a server that’s authorised to sign these status responses on the CA’s behalf. This allows the responder to prove that its answers are genuine without exposing the CA’s private key.

By checking both validity dates and OCSP revocation status, systems like Plug & Charge ensure they only trust certificates that are both current and still approved by the CA.

Note that OCSP responder certificates are used by all entities in the Plug & Charge ecosystem – including CPS, MSPs, and OEMs – but are shown only once in the diagram for simplicity and clarity.

Additional certificates in ISO 15118-20

ISO 15118-20 brings several notable cybersecurity enhancements, which we briefly covered in the previous article. For now, let’s focus on the changes affecting the digital certificates.

Additional Vehicle Certificates for mutual TLS

You’ll notice an additional blue strain in the vehicle manufacturer PKI hierarchy. Those additional Vehicle Certificates were introduced to enable mutual TLS authentication, meaning that authentication now happens in both directions – the EV must also prove its identity to the charger, not just the other way around.

OCSP responder certificates for leaf certificates

It always seemed like an odd design choice that ISO 15118-2 used OCSP responder certificates only for Sub CAs, not for the leaf certificates such as SECC or contract certificates. The rationale was that some leaf certificates are typically short-lived – e.g. SECC certificates are valid for just a few months – making the overhead of maintaining and querying OCSP responders less justified.

Still, to close this potential revocation blind spot, ISO 15118-20 now includes OCSP responder certificates at all levels, ensuring that even short-lived leaf certificates can have their revocation status checked if needed.

Note that OCSP responder certificates are used by all entities in the Plug & Charge ecosystem in ISO 15118-2 and -20 – including CPS, MSPs, and OEMs – but are shown only once in the diagram for simplicity and clarity.

Cross-certification and Certificate Trust Lists (CTLs)

In ISO 15118-20, cross-certificates were introduced to bridge trust between separate PKI hierarchies – for example, when two different V2G Root CAs need to recognise each other. When one V2G Root CA cross-signs another’s public key, an EV that only trusts e.g. a V2G Root CA from Hubject can still authenticate a charger whose certificate chain originates from Irdeto’s V2G Root CA.

As a result, the updated standard permits certificate chains of up to four certificates instead of three: the leaf certificate, two Sub CAs, and additionally one optional cross-certificate.

Wait, but what about the Root CA certificate? Isn’t that part of the certificate chain?

Ahh, now that’s important to remember: a Root CA certificate is never sent as part of a certificate chain, because Root CAs are trust anchors that need to be pre-installed on the verifying device – such as an EV or charger – to enable the verification of the received certificate chain (leaf → Sub CA 2 → Sub CA 1).

However, this cross-certification setup adds significant complexity to trust validation and certificate management, which is why the industry is moving instead toward Certificate Trust Lists (CTLs) – a simpler way to publish trusted Root CAs. The EU’s Sustainable Transport Forum (STF) is currently defining a PKI interoperability governance directive, which we’ll probably touch on in next week’s article.

Certificate size increased

In ISO 15118-20, the maximum allowed X.509 certificate size increased to 1,600 bytes (previously 800 bytes in ISO 15118-2). This change was introduced to accommodate the richer data (e.g. more detailed subject/issuer fields) and modern cryptographic algorithms required (e.g. stronger elliptic curves such as secp521r1 or Ed448).

This becomes an important consideration when determining how much memory your EV or charger should include before it goes to market.

And that’s a wrap for today. Or, as Master Yoda would say: “A PKI mastered, you have.”

You’re now armed with the essentials to understand how a Plug & Charge session unfolds – from signing that EV electricity contract all the way to plugging in and watching the electrons flow.

Next week, we’ll peek into the ISO 15118-20 PKI (spoiler alert: it adds a few extra certificates) and unpack the storage requirements for EVs and chargers to manage both PKIs – an important design decision you want to get right in order to support both ISO 15118-2 and -20. We’ll also trace the full journey of a contract certificate – from issuance to installation to authentication at the charger – and watch a Plug & Charge session in action, start to finish.

Stay tuned, it’s going to the be finale of the Plug & Charge article series for now – before I take you onto the next journey: smart charging and vehicle-to-grid (V2G).