Preparing an EV for Plug & Charge: what really happens behind the scenes

A step-by-step look at the orchestration of digital certificates, billing contracts, and market roles that enables seamless Plug & Charge across the entire industry.

This article tells the story of how the simplest and most secure form of authentication at an EV charging station is actually the result of a fairly sophisticated orchestration of and collaboration between various players in the e-mobility market.

How a physical vehicle becomes a digital charging identity. How a billing relationship is transformed into a cryptographic contract. How that contract is securely delivered into your car – sometimes quietly in the background, sometimes live at the charging station – so your EV can use it to authenticate and authorise on your behalf in a matter of seconds.

Bringing home the same “just plug and go” experience Tesla drivers have experienced for a long time – but enabled across all EV and charger brands.

Throughout this article, I’ll link back to the first three chapters of this five-part Plug & Charge series. Those earlier pieces introduced the market roles, the cryptographic building blocks, and the digital certificate ecosystem (think PKI) that make everything work. This article brings those threads together so the “magic” of Plug & Charge finally feels tangible and real.

You plug in your car. And charging just… starts.

To the driver, this feels effortless. You don’t even need to go inside the kiosk to pay for the electricity.

To the system behind it, this is one of the most carefully choreographed trust exchanges in the entire energy and mobility ecosystem. What looks like a single moment of convenience is actually the result of a multi-party cryptographic provisioning process that began long before that cable ever touched the socket.

Let’s unpack what really happens before Plug & Charge ever becomes “just plug in and go”.

How your EV turns into a digital charging identity

One of the most important steps in Plug & Charge doesn’t happen at a charging station. It happens before the car is even sold.

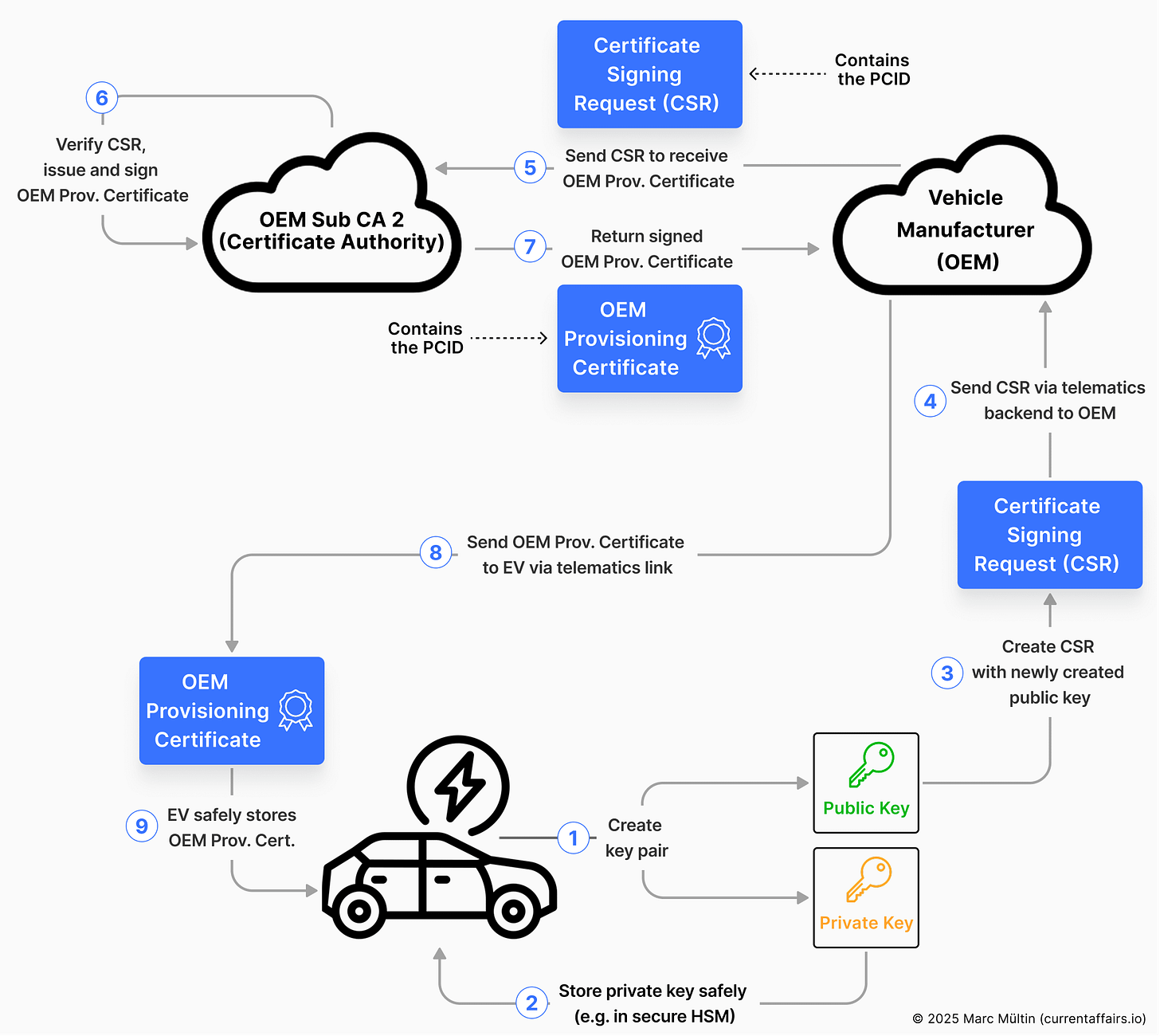

Step 1: Create vehicle identity & install trust anchors

When a vehicle leaves the factory, it already carries:

A unique digital identity called Provisioning Certificate ID (PCID), which is tied to that exact physical vehicle

A public–private key pair generated securely inside the car

An OEM provisioning certificate issued by the manufacturer, which contains both the PCID (in its Subject attribute1) and the newly created public key – this certificate is basically the vehicle’s own “digital passport”

And one or more V2G root CA certificates that tell the car which charging infrastructure it is allowed to trust. Go check this section in the previous article if you don’t know or remember what I mean by V2G root CA certificate.

This is the EV equivalent of pre-installing trusted website identities into your web browser. Without these trust anchors, the car would have no way of knowing whether a charger is legitimate or a fake designed to intercept data.

The vehicle manufacturer also uploads the OEM provisioning certificate, along with its OEM Sub CA certificates, to a database called the Provisioning Certificate Pool (PCP), operated by the PKI provider. The MSP will need access to this certificate chain, as you’ll see in the next step.

The illustration below focuses on the vehicle manufacturer’s steps to create an OEM provisioning certificate and to store it in the vehicle for which it was issued.

There are several Plug & Charge PKI providers operating globally, each offering their own V2G root certificate authority (CA). In Europe, we have Hubject, Irdeto, and Gireve. In North America, the landscape includes Hubject, Irdeto, SSI, and DigiCert.

From what I understand, car manufacturers don’t install all of these by default. Instead, the choice of which V2G root CAs to embed is largely driven by where the vehicle is sold. A car delivered in Europe is unlikely to need the North American trust anchors, and vice versa.

All right, let’s move on. At this stage, the car doesn’t yet know who will pay for charging.

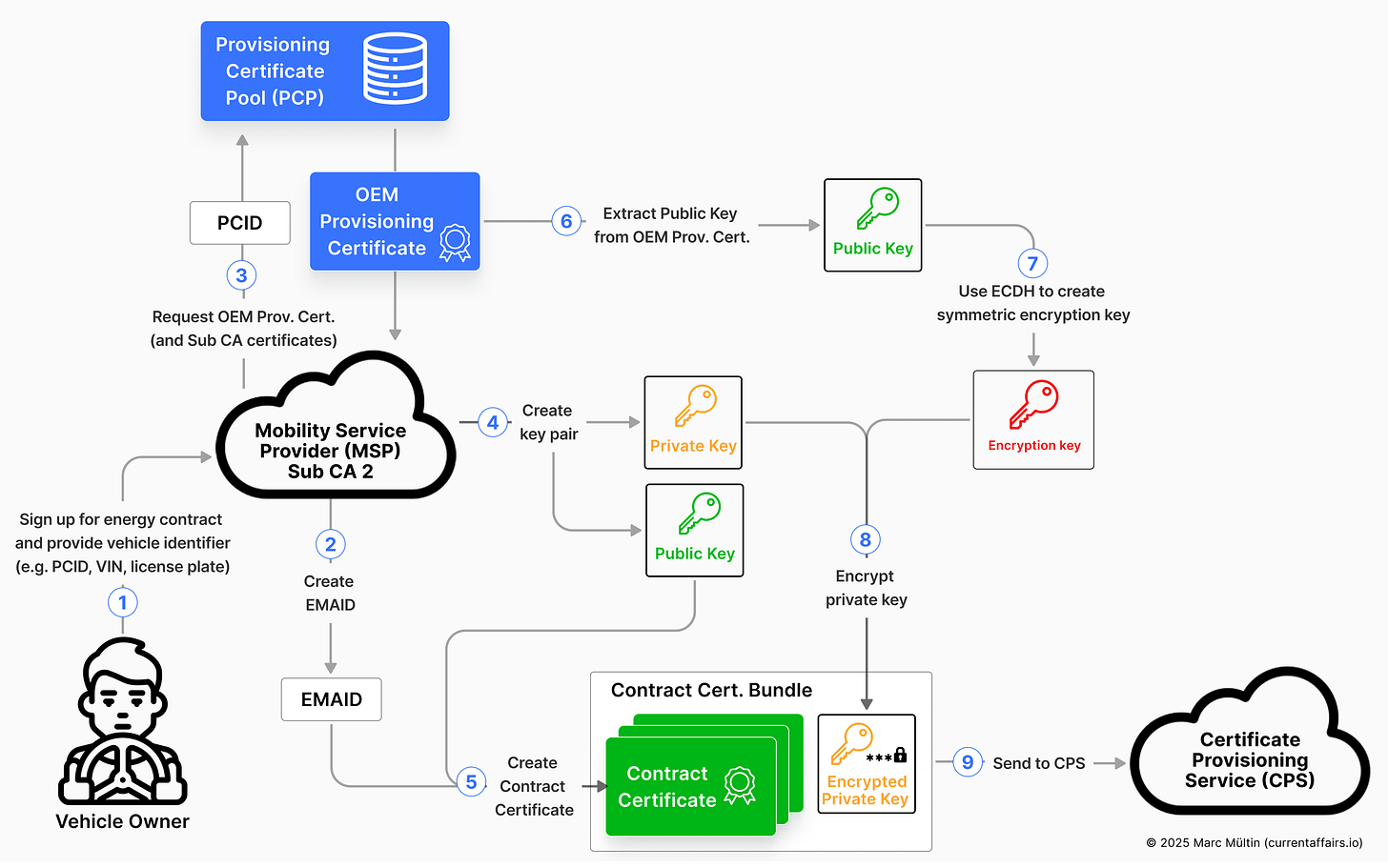

Step 2: Linking the MSP to the vehicle’s unique identity

The mobility service provider (MSP) is the market role that provides the billing account for the energy your vehicle charges during a Plug & Charge session. The single most important piece of information the MSP needs from the vehicle owner is the PCID – the provisioning certificate ID that uniquely identifies the specific vehicle being enabled for Plug & Charge.

In the cleanest implementation, the vehicle owner retrieves this PCID directly from the car’s app or from documentation supplied by the manufacturer. But in practice, some MSPs deliberately abstract this complexity away from the user and accept more familiar identifiers instead, such as the vehicle registration number or even the VIN (vehicle identification number). Octopus Electroverse, a pioneer on Plug & Charge on the MSP side, follows this approach in its Plug & Charge onboarding flow.

“We’re big believers in Plug & Charge as the eventual industry-wide answer to simple consumer charging.”

– Matt Davies, Founder & Director at Octopus Electroverse

In the UK, this works because MSPs can – under tightly regulated conditions – query the DVLA (Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency). The DVLA is the government body that holds the authoritative register of all vehicles and registered keepers. By resolving a number plate against DVLA records, the MSP can indirectly determine the underlying PCID it actually needs.

Why does that PCID matter so much?

Because it is the lookup key that allows the MSP to retrieve the car’s OEM provisioning certificate and related OEM Sub CA certificates from a dedicated database called the Provisioning Certificate Pool (PCP).

And crucially, the MSP uses the public key inside the OEM provisioning certificate later to establish a secure encryption key with the vehicle (using an ECDH-style key agreement). That shared key is then used to encrypt the vehicle’s private signing key when the contract certificate is created. This signing key is the private counterpart to the public key embedded in the contract certificate itself.

Step 3: Turning the billing contract into a cryptographic ID

Once the MSP has both:

a confirmed PCID, and

proof that the driver is entitled to use the vehicle,

it can begin creating the digital object that actually enables seamless Plug & Charge: the contract certificate.

The first thing the MSP generates is the E-Mobility Account ID (EMAID). This is the globally unique identifier that’s tied to the charging contract, think of it as the billing account ID. The structure of an EMAID is defined in ISO 15118 and it encodes:

the country the mobility service provider is registered in,

the MSP’s provider ID,

and the unique billing account instance.

Several countries have established identifier registries for businesses where you can look up both operator IDs (for CPOs) and provider IDs (for MSPs). In the UK, for example, it’s the EV Roam registry, in Germany it’s the Energy Codes & Services GmbH.

To stay with the Octopus Electroverse example from above, a valid EMAID could be GB-OCT-C1234ABCD (with GB-OCT being Octopus’ provider ID in the UK).

At this point, the EMAID represents a commercial relationship. Next, the MSP:

Requests the OEM provisioning certificate (and the connected OEM Sub CA certificates2) from the provisioning certificate pool, using the PCID supplied during signup as a lookup key.

Generates a brand-new public–private key pair that will represent the cryptographic identity of the charging contract.

Issues and signs the contract certificate (see an example here), binding together:

the newly generated public key,

and the EMAID (in the Subject attribute).

Now comes one of the most security-critical steps in the entire system.

The private key must be transferred to the vehicle – but in a way that ensures only that specific EV can ever use it.

To achieve this, the MSP:

takes the public key from the OEM provisioning certificate,

uses it to establish a secure encryption key with the vehicle in order to encrypt the newly created private signing key that’s mathematically linked to the contract certificate’s public key3,

and then permanently deletes its own unencrypted copy of that private key.

From this moment onward, the MSP is cryptographically locked out. The EV alone will be able to use that private key to create digital signatures for Plug & Charge authentication at the charging station.

The contract certificate (plus the linked MSP Sub CA certificates) and the encrypted private key are now, together with a few other data elements, assembled into a data package called contract certificate bundle, which is then sent to the certificate provisioning service (CPS).

The illustration below summarises the MSP’s role outlined in steps 2 and 3 above. I’ve intentionally abstracted a few details of the contract certificate bundle that aren’t essential to understanding the flow and only really matter during implementation.

(Update 17/12/2025: The image below and description above were slightly updated to reflect that the MSP does not need to verify the OEM’s certificate chain itself, as it relies on the provisioning certificate pool to have already performed that validation.)

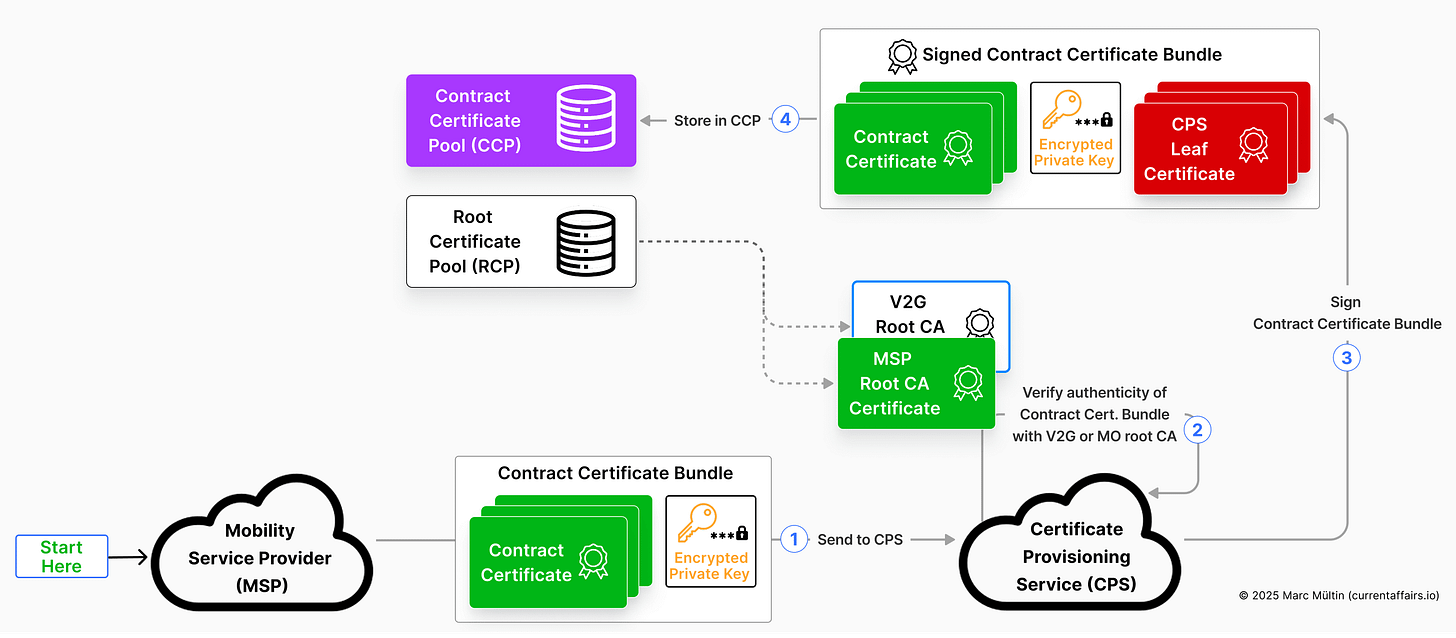

Step 4: Certificate Provisioning Service & transitive trust

In deregulated markets like Europe, the charge point operator (CPO) and the mobility service provider (MSP) must be legally separate entities. That separation makes trust a bit more complicated.

In theory, every MSP could operate its own root certificate authority (as discussed in the last article) but that would force car manufacturers to preload potentially dozens or hundreds of MSP trust anchors into every vehicle. The resulting memory and update management would quickly become impractical, especially given the high cost and strict optimisation requirements in automotive electronics.

The CPS solves this through transitive trust.

It operates under a V2G root CA that the EV already trusts (pre-installed) and:

verifies the MSP’s contract certificate chain, for which it uses the V2G (or MSP) root CA certificate that’s stored in a database called Root Certificate Pool (RCP) – every PKI provider, be it Hubject, Irdeto, Gireve or others, operate an RCP, which stores the relevant Plug & Charge root CA certificates,

re-packages and digitally signs the contract certificate bundle,

and stores the final, signed contract certificate bundle – which also contains the CPS certificate chain for the signature verification later on – inside another database called Contract Certificate Pool (CCP).

From the EV’s point of view, this means: “I don’t need to trust every MSP on earth, only the one I already know.”

And that single design decision is what allows Plug & Charge to scale globally without collapsing under certificate chaos.

The illustration below summarises the CPS’s steps we just discussed.

Step 5: How the certificate actually enters the car

By the time we reach this stage, the heavy lifting is done. The contract certificate exists. The associated private key has been generated, encrypted specifically for one single vehicle, and wrapped into a signed data package by the certificate provisioning service. All of this now sits ready inside the contract certificate pool, which is a database operated by the PKI provider (like Hubject, Irdeto, or Gireve).

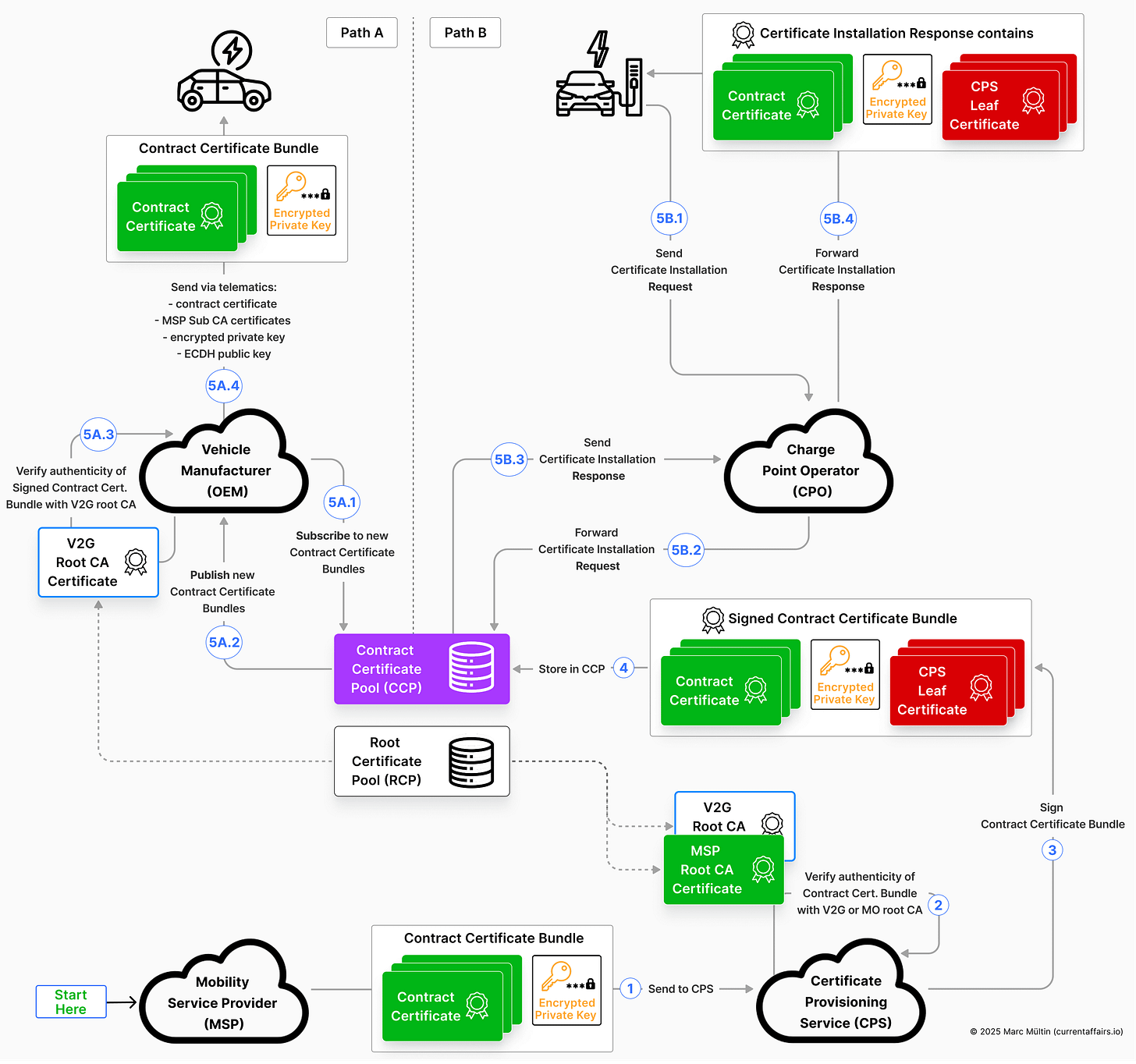

What remains is the final and most visible step: getting that cryptographic identity into the vehicle itself. And interestingly, the ecosystem supports two fundamentally different installation paths.

Path A: Over the air via the car manufacturer

If a vehicle manufacturer supports over-the-air (OTA) installation via its telematics backend, it can subscribe directly to updates from the contract certificate pool. The moment a new certificate becomes available for one of its vehicles, the OEM backend is notified immediately – implemented either via a publish-subscribe mechanism or webhooks.

From there, the manufacturer:

retrieves the signed contract certificate bundle (signed by the CPS),

checks the authenticity of this data package by verifying its digital signature with the CPS certificate chain (included in the data package) and the right V2G root CA certificate (received from the PKI provider’s Root Certificate Pool),

retrieves the encrypted private key, contract certificate, and the extra information the vehicle needs to decrypt that private key – the ECDH public key generated by the MSP during encryption,

securely transfers them to the vehicle via its own cloud infrastructure,

and lets the vehicle perform the final step locally: decrypting the private key and storing it alongside the contract certificate inside the car.

The car manufacturer controls the entire user journey and can integrate Plug & Charge activation seamlessly into the app and/or in-car user experience.

From the driver’s perspective, Plug & Charge simply “appears” one day, no charger interaction required.

Here’s a great video from BMW on how to activate and use Plug & Charge. BMW has gladly understood the importance of letting the vehicle owner decide which MSP contract they prefer to use, and when. They support up to five contracts, including their own MSP service which is facilitated through Digital Charging Solutions.

Path B: Live installation at the charging station

The second path is the classic ISO 15118 flow, using the Certificate Installation Request / Response message pair specifically designed for this scenario.

Here, the installation happens in real time, at the moment the vehicle is plugged in – if the charging station supports contract certificate installation, which is one of several possible value-added services the charger can offer. The Certificate Installation Response basically carries all the data elements contained in the signed contract certificate bundle, just packaged in the right ISO 15118 message format.

But because of the tight timing constraints in ISO 15118, this method is far from ideal in my opinion. As soon as the EV sends its Certificate Installation Request, a five-second timer starts. If the response doesn’t arrive within that time window, the procedure fails. In ISO 15118-2 this is especially brittle, because the vehicle must abort after five seconds, even though the Certificate Installation Response can be several kilobytes in size and may take longer to retrieve over a slow or congested network. ISO 15118-20 softens this behaviour: instead of giving up after five seconds, the vehicle is allowed to keep waiting for the response.

As this path is likely going to be less common in the future (to the point that I assume all car manufacturers will converge to OTA installation), I’ll not dive into any further details about this installation path.

To bring it all together – and untangle any knots this deep dive might have created – I’ve put together a visual summary of the flow we just covered in Step 4 and Step 5. I’ve left out smaller details like the ECDH public key to keep the illustration readable, but you’ll find those explained in the text above.

When all of this disappears into a single moment

Once the contract certificate is installed – whether via the vehicle’s telematics link or live at the charger – the system finally reaches the state the driver always assumed it was in from the beginning:

the car now holds a valid cryptographic charging identity (contract certificate),

it can authenticate automatically upon plugging in the cable (using the private key to create digital signatures that can then be verified with the contract certificate),

and the vehicle owner’s billing account (identified via the EMAID) can be billed without any further human interaction.

From that moment onward, Plug & Charge feels simple.

But what makes it remarkable is how much coordination, cryptography, and infrastructure silently converge just to make that simplicity – enabled by automated and secure machine-to-machine communication – possible.

Congratulations! You now know all the steps that need to happen prior to a Plug & Charge session. In my next article, which will conclude this Plug & Charge series, we’ll finally go through how a Plug & Charge session actually works.

One language to coordinate all market roles

Now that you know what the car manufacturer, mobility service provider, certificate provisioning service, and charge point operator need to do orchestrate the provisioning and installation of a digital contract certificate, the question becomes: how are they going to communicate with each other?

What does this mean for you, as someone tasked with “making Plug & Charge work”. Is there a standardised “language”, an agree-upon unified protocol you can leverage?

An open Plug & Charge testing environment

Thankfully, there is. Or at least we’re on the way to creating one.

Early 2022, Hubject introduced an open-source protocol called Open Plug and Charge Protocol (OPCP). The purpose of the OPCP protocol is to provide an open, international, supplier-agnostic API framework that enables seamless interoperability across Plug & Charge systems, linking multiple PKI ecosystems, CPOs, MSPs and OEMs so that EVs, chargers and backend networks can operate together smoothly.

To help familiarise yourself with OPCP, Hubject created a public Plug & Charge testing environment where you can freely interact with their PKI ecosystem. It’s a testing playground where you can impersonate any of the market roles we discussed above and create various kinds of certificates, access the data pools that store these certificates, and explore the API interface of OPCP to interact with their PKI system.

OPNC: The path to a fully interoperable solution

In 2024, CharIN e.V. established a task force to take over the governance of this open-source project and changed the protocol name to Open Plug & Charge Network Communication Protocol, or OPNC (link to GitHub repo) for short.

I know, it’s becoming a bit of a joke with all those protocol acronyms that all have an ‘O’, ‘P’, and ‘C’ in it. But fear not, I’ve prepared an Acronym Survival Guide for you.

The OPNC task force is currently paused until March 2026 while Hubject, Irdeto, and Gireve run their interoperability pilot – a phase meant to generate real-world insights before any new protocol work continues. OPNC 1.0 was never implemented by the industry, largely because it offered no practical value over OPCP and supposedly suffered from robustness and security issues. The hope is that this pilot will inform a completely reworked OPNC 2.0 that is genuinely secure, multi-supplier compatible, and worth implementing.

What the Hubject–Irdeto–Gireve partnership actually delivers

The partnership between Hubject, Irdeto, and Gireve effectively allows CPOs, MSPs and vehicle OEMs to simply choose which Plug & Charge PKI provider they want to work with out of the three, and they’ll gain access to the other two Plug & Charge ecosystems as well. Technically, mutual API integrations connect the PKI pools into one interoperable network, allowing all three partners to exchange provisioning certificates (PCP), contract certificates (CCP), and root certificates (RCP) seamlessly.

For MSPs, this is a major win: they can now create contract certificates on any of the three PKI providers, regardless of where the vehicle’s OEM provisioning certificate is stored. The system takes care of the rest: it makes sure the contract certificate is signed by the CPS that’s linked to the same V2G root CA the vehicle already trusts, and finally delivered to the vehicle either via CPO-triggered installation or through existing OEM telematics integrations.

Car OEMs see little day-to-day change, except that all their vehicles’ provisioning certificates become visible across all three PKI providers. And CPOs gain the ability to perform contract certificate installations for any contract certificate, no matter which PKI provider’s contract certificate pool (CCP) issued or stores it.

In summary, all three providers have connected their PCP and CCP data pools, audited one another, and also retrieve each other’s root CA certificates on demand. The partnership dissolves the old PKI silos, enabling true cross-provider Plug & Charge certificate creation and installation.

And that brings us to the end of today’s story — a look at how Plug & Charge comes to life through the carefully choreographed collaboration of all the e-mobility players involved.

My next article will conclude this five-part Plug & Charge series. In this final missing piece you’ll find out what actually happens at the charger when you plug in the cable and the EV automatically authenticates and authorises itself for energy delivery without you having to do anything.

You never know when this stuff will come in handy – your next job interview, a tricky internal project, or that conference where you get to wow people with unexpectedly deep Plug & Charge knowledge. (I’d be keen to hear some anecdotes from you).

So stay tuned, and please do share this newsletter with anyone who you believe could benefit from it. Let’s work together to make Plug & Charge ubiquitous!

Check out the section on “How does a digital certificate look like” from last week’s article if you need a refresher on the contents of a digital certificate.

You may wonder Why we are using Sub CAs in a PKI? Check out the link to get a clear answer to this very natural question.

Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) comes into play to create the symmetric session key used to encrypt the private key on the MSP side and later decrypt it on the vehicle’s side.