How a Plug & Charge session actually works

Learn how the EV automatically authenticates itself at the charging station, what security checks unfold, and what vehicle and charger OEMs need to consider in terms of memory capacity.

This is the final chapter of my five-part Plug & Charge series. The point where everything we’ve explored so far finally converges into the single moment you plug in your EV and experience the most seamless way of EV charging.

In Part 1 of my Plug & Charge article series, we mapped out the market roles, the state of play of Plug & Charge in 2025, and the regulatory dynamics (e.g. AFIR, NEVI) across the globe. In Part 2, we went down into the cryptographic engine room: the foundational cybersecurity concepts that enable confidentiality, authenticity and data integrity, like public-private key cryptography and digital signatures. And in Part 3, we explored what “trust” really means in a machine-to-machine world and got introduced to the concept of digital certificates and public key infrastructures (PKIs). These PKIs form the architecture that facilitates trust and authentic communication between all market roles involved in making Plug & Charge a reality, worldwide.

In last week’s Part 4, we explored how the all-important contract certificate finds its way into your vehicle. This contract certificate is the EV’s charging identity or “passport”, and it’s linked to a billing account of your chosen mobility service provider (MSP).

The final missing piece in this Plug & Charge article series is what actually happens at the charger when you plug in the cable and the EV automatically authenticates and authorises itself for energy delivery without you having to do anything.

No apps. No cards. No QR codes needed to start charging. This is where it all finally comes together.

How a Plug & Charge session actually works

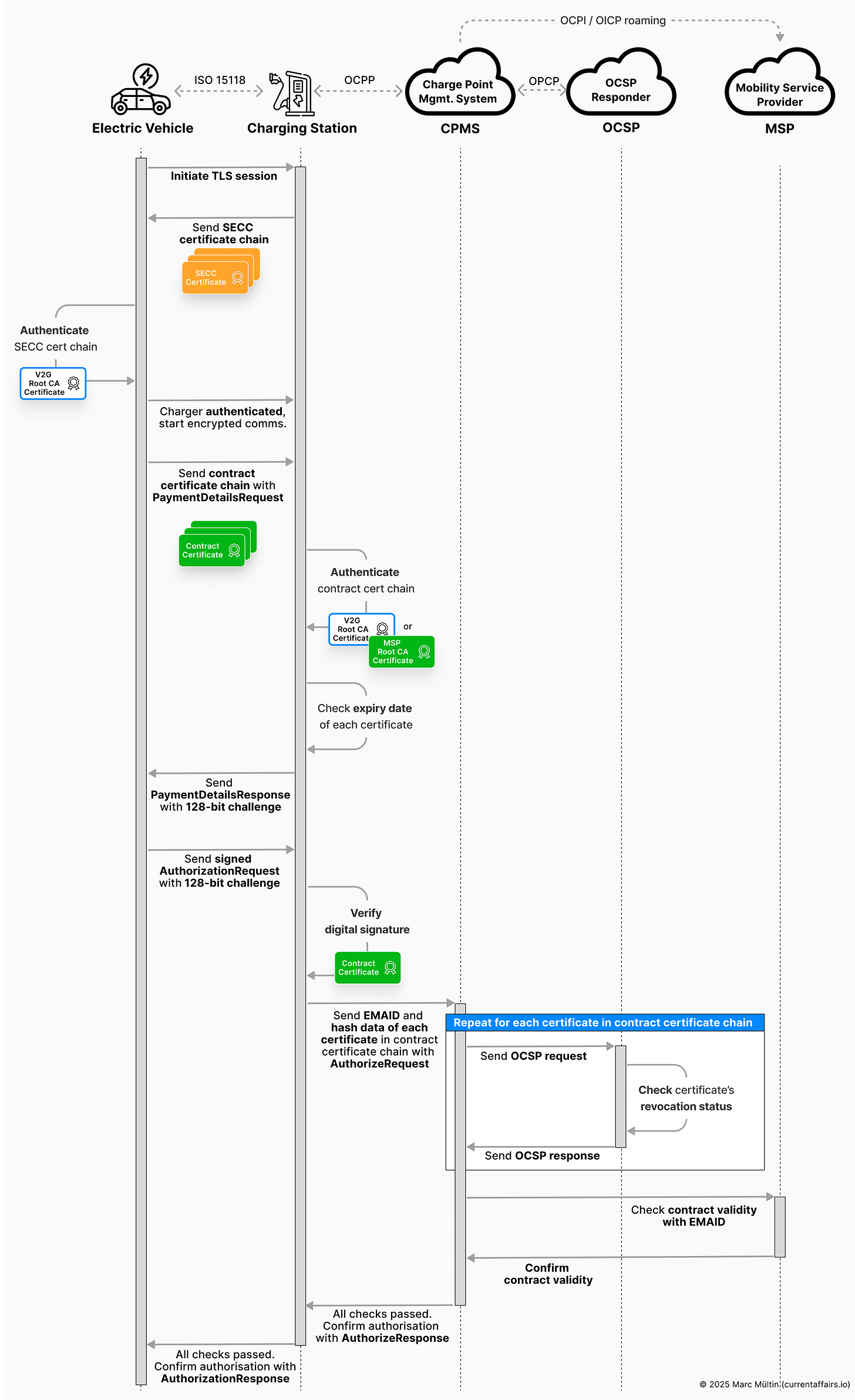

Once a contract certificate is inside the vehicle, the magic of Plug & Charge plays out in three choreographed phases every time you plug in.

1. First, the car and charger build trust

It starts with the EV and the charger establishing a secure communication channel. After you plug in and the digital communication link is set up, they negotiate the version of TLS (Transport Layer Security) to use: TLS 1.2 for ISO 15118-2 or TLS 1.3 for ISO 15118-20.

The charger then presents its certificate chain – the SECC certificate and the CPO Sub CA certificates – to identify itself to the EV as a trustworthy charger. The same principle is at play when you surf any https-secured website these days. The charger is basically the equivalent of a web server in this analogy. In case you need a refresher on the various certificates that belong to each EV charging market role, check out my section on the ISO 15118 PKI ecosystem.

The EV then checks the entire chain against its pre-installed trust anchor, which is the V2G root certificate that was installed in the car before it was delivered to a customer – just like your browser checks a website’s certificate before loading a page. You may also want to refresh your understanding on the chain of trust from leaf certificate to trust anchor if that concept still feels a bit unclear.

Only ISO 15118-20 supports mutual authentication, whereby the vehicle also authenticates itself to the charger sending a Vehicle Certificate chain.

The EV also performs revocation checks: ISO 15118-2 relies on short-lived (2-3 months) SECC certificates and uses OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol) validation for the CPO Sub CA certificates, while ISO 15118-20 mandates OCSP for all certificates.

Once everything checks out, the EV accepts the charger as trustworthy and the rest of the conversation is encrypted.

2. The car and charger agree on the identification method

ISO 15118 supports two ways to identify the driver during a charging session:

EIM (External Identification Means): RFID, credit card, app, QR code

Plug & Charge: Fully automated certificate-based authentication

The crucial detail: the charger must not identify the driver twice.

If a driver taps an RFID card first and then plugs in, the charger should not offer Plug & Charge anymore; otherwise, the EV might also authenticate using its contract certificate, creating the risk of duplicate billing.

A sensible approach is:

If the driver authenticates via EIM first → disable Plug & Charge for this session.

If the cable is plugged in first → offer both.

If Plug & Charge fails due to an expired or invalid certificate → fall back gracefully, reset, and give the EV another chance or offer EIM as backup.

Designing this identification logic well makes the difference between effortless charging and user confusion.

Step 3: The car proves who it is

Once Plug & Charge is selected, the EV presents its contract certificate – along with the MSP Sub CA certificates, all packaged up nicely in a certificate chain – to the charger, and this is where the real authentication happens. Behind the scenes, several security checks unfold, each designed to ensure the session is legitimate, the billing account is valid, and no one is trying to impersonate the vehicle.

1. The charger verifies the certificate chain

The charger or CPO backend checks:

Validity: none of the certificates in the chain have expired

Authenticity: every signature from the contract certificate up to the root is valid

These checks can – and should – be performed locally on the charger. A prerequisite for that is that the charger has the correct root certificates installed – typically one of the V2G root CAs provided by the PKI operators, or in rarer cases an MSP’s own root CA (less likely). If those certificates aren’t available locally, the charger must send the contract certificate chain to the CPO backend for verification, usually via OCPP 2.0.1 (or, less ideally, via OCPP 1.6 with security extensions, which can introduce interoperability issues).

I highly recommend doing this verification step locally (on the charger) as these certificate chains are several kilobytes in size and can delay the charging process depending on the charger’s internet connectivity and data congestion. Otherwise, you risk negatively impacting the user experience.

2. The charger checks for revocation

Some checks must be online. One of them is certificate revocation. The charger queries the OCSP responder listed in the certificate to make sure that:

the CPO Sub CA certificates (ISO 15118-2 and -20), and

the contract certificate (ISO 15118-20 only),

have not been revoked. Without this, a compromised or invalid certificate could still authenticate.

Hubject’s Requirements EVSE CHECK for Plug & Charge with ISO 15118-2

Hubject currently provides a Plug & Charge (PnC) certification program for EV chargers called EVSE Check, which has helped accelerate early adoption.

As such, Hubject published a requirements document that every charger manufacturer and CPO must study closely because it defines the exact security and process steps required for a seamless, interoperable Plug & Charge experience across the ecosystem.

For example, section 2.8 “Performing PnC related OCPP messages” stipulates that a charger should verify the contract certificate chain locally because it already holds the V2G / MSP root certificates needed for validation, making the process faster without burdening the network.

The CPMS does not need the full certificates, only their (significantly smaller) hash data, which uniquely identifies each certificate and is sufficient for OCSP responders to check their revocation status. Sending the full certificate chain would add no security value while significantly increasing message sizes and communication overhead.

The OCPP configuration key CentralContractValidationAllowed specifies whether the backend is allowed to receive full certificates; if this key is not set, the charger must default to local validation of all the signatures along the certificate chain and send only hash data in the AuthorizeRequest to check each certificate’s revocation status. This ensures consistent behaviour, reduced bandwidth usage, and a smoother, faster Plug & Charge flow.

3. The charger verifies the billing account

Trust in the certificate alone, which represents the charging identity, is not enough. The charge point operator (CPO) also needs to know that the billing contract is still active.

Using the provider ID inside the E-Mobility Account Identifier (EMAID), the CPO’s backend – also known as Charge Point Management System (CPMS) – contacts the correct MSP to confirm that the account hasn’t been suspended or cancelled. This is a crucial business step: no CPO wants to deliver energy without knowing they’ll be paid for it.

And how does the CPO get in contact with the right MSP, based on this EMAID?

That’s where roaming protocols comes into play. The CPO uses either a roaming hub like Hubject (which currently only supports their proprietary OICP protocol) or the peer-to-peer roaming protocol OCPI (Open Charge Point Interface). The latter is becoming more and more an industry standard, which is why Hubject finally announced their support of OCPI in September 2025. According to my sources, it’ll probably take until the end of 2026 until Hubject fully supports OCPI as well.

4. The system prevents replay attacks

To ensure no attacker can “replay” a previously captured authorisation message, ISO 15118 uses a challenge-response mechanism. The charger sends a secure and randomly generated 128-bit value (the “challenge”). The EV must include this challenge in its Authorization Request message and sign the message using the private key linked to its contract certificate.

The charger verifies this signature using the contract certificate’s public key. No backend is needed here – just proper cryptography and a secure random number generator. For data privacy and security, the EV’s contract certificate must not remain stored on the charger once the session ends.

5. And then charging can finally begin

Once all checks pass – certificate chain validation, revocation, billing account status, and replay protection – the EV is authenticated. Only then do the EV and charger continue with the ISO 15118 message flow to negotiate charging parameters and charging schedules.

The sequence diagram below summarises the relevant steps of the authentication and authorisation flow we just discussed. It illustrates the activities of each involved party – EV, charger, CPMS backend, OCSP responder, mobility service provider – and the communication protocols used to exchange the data.

Does Plug & Charge work if the charger is offline?

Technically yes, but not without disregarding the above mentioned security checks.

A charger can authorise offline, but it’s risky: the billing account might later turn out to be suspended.

A pragmatic approach is:

allow Plug & Charge when offline only if the certificate has not previously caused a failed billing validation,

otherwise fall back to EIM (e.g. using a local RFID allowlist) until the charger is online again.

This approach keeps drivers charging while still protecting the CPO against repeated losses.

Operational takeaways for OEMs and CPOs

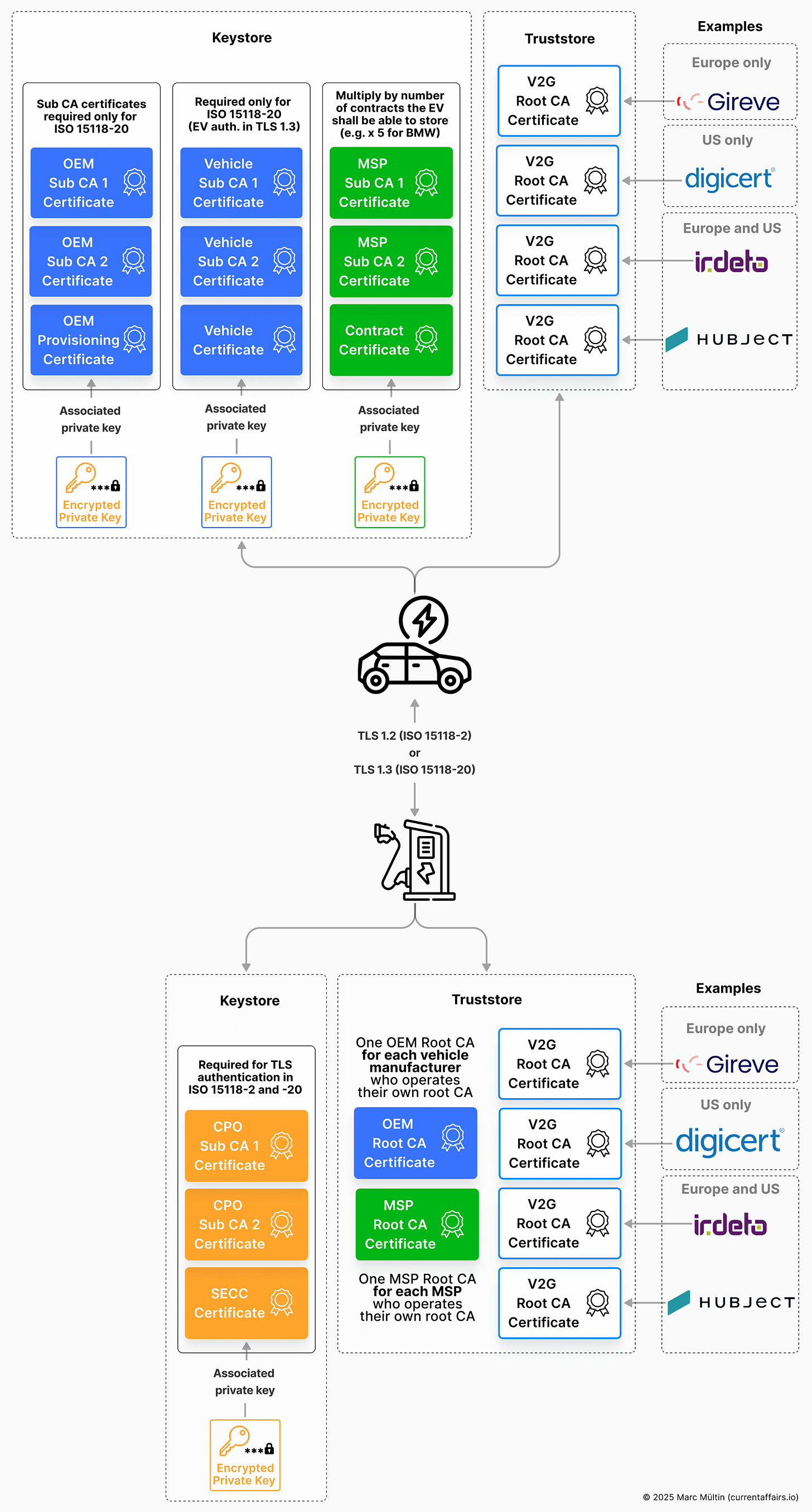

Let’s clarify what cryptographic material must live inside an EV and a charging station to establish a secure TLS 1.2 (ISO 15118-2) or TLS 1.3 (ISO 15118-20) connection and to provision, store, and validate the contract certificate(s) for Plug & Charge.

In TLS (Transport Layer Security), each side needs two distinct sets of data: identity material (often called a keystore) and trust material (often called a truststore).

The keystore holds the device’s private key and its corresponding leaf certificate, usually together with any required intermediate (Sub CA) certificates, and represents “who I am.”

The truststore contains trusted CA certificates (trust anchors) used to verify the other party’s certificate and answer “who do I trust” (see my explainer on chain of trust).

While the terms keystore and truststore are common (and well known from Java), you may also see the same concepts described as private key + certificate chain, identity, CA bundle, root store, or trust anchors in C, C++, Rust, and embedded TLS stacks.

The image below illustrates where each cryptographic key material and digital certificates need to sit. This becomes an important consideration when determining how much memory your EV or charger should include before it goes to market.

It is difficult to specify an exact number of certificates that must be stored in a Plug & Charge-enabled EV or charger brought to market. Instead, the following guidelines can be used to size the required certificate storage appropriately:

General considerations

While ISO 15118-2 allows for maximum certificate sizes of 800 bytes, in ISO 15118-20 the maximum allowed certificate size increased to 1,600 bytes. This change was introduced to accommodate the richer data (e.g. more detailed subject/issuer fields) and modern cryptographic algorithms required (e.g. stronger elliptic curves such as secp521r1 or Ed448).

Certificates issued for ISO 15118-2 cannot be reused for ISO 15118-20. Each standard version requires its own dedicated certificate hierarchy, including separate leaf and Sub CA certificates.

For example, an OEM provisioning certificate issued for ISO 15118-2 is valid only for that version and must not be used for ISO 15118-20. Supporting both standards therefore requires installing and managing two parallel certificate sets – one for ISO 15118-2 and one for ISO 15118-20.

All cryptographic key material on the EV or charger should be stored in a hardware-backed secure element – e.g. TPM 2.0-compliant device or Hardware Security Module (HSM) – that enforces non-exportable keys and protected cryptographic operations.

Memory storage for EVs

The OEM provisioning certificate only needs to be stored on the EV if the vehicle manufacturer intends to support contract certificate installation via the charging station using ISO 15118. If the contract certificate is provisioned exclusively via over-the-air (OTA) updates, the OEM provisioning certificate only needs to reside in the cloud-based Provisioning Certificate Pool (PCP) (see here for a refresher on PCP).

The same applies to the OEM Sub CA certificates. These certificates must be installed on the EV only if the vehicle supports ISO 15118-20 and contract certificate installation via the charging station is enabled as a feature. Otherwise, they can remain solely in the PCP.

According to Steffen Rhinow, Director Plug & Charge at Hubject, the prevailing trend is to provision contract certificates exclusively via OTA updates rather than through the charging station.

The Vehicle Certificates were introduced with ISO 15118-20 to enable mutual TLS authentication. Mutual authentication means that authentication now happens in both directions – the EV must also prove its identity to the charger, not just the other way around. Vehicle certificates are not used in ISO 15118-2.

The more MSP contracts an EV driver is allowed to use with their EV, the more contract certificate chains (leaf + two Sub CA certificates) need to be stored on the EV.

For example, if a vehicle allows up to five MSP contracts and supports both ISO 15118-2 and -20, then worst case you need to account for a maximum of5 x 3 x 800 bytes (five ISO 15118-2 contract certificate chains)

+ 5 x 3 x 1600 bytes (five ISO 15118-20 contract certificate chains)

= 36 kilobytes for contract certificates.

Each EV must have sufficient storage to hold all relevant V2G root CA certificates for the region in which it is sold. OEMs do not embed all global V2G root CAs by default; instead, the selection is driven by the vehicle’s target market.

For example, an EV sold in Europe typically does not require North American trust anchors, and vice versa. Based on the illustration above, an EV sold in Europe should be capable of storing at least three V2G root CA certificates – one each from Hubject (current market leader), Irdeto, and Gireve. In addition, storage must account for a transitional period of roughly one year during which an expiring trust anchor and its replacement coexist. I’d say storage for five to six trust anchors should be sufficient.

The current reality is that only Hubject’s V2G root CA is installed in Plug & Charge enabled EVs. Time will tell when Iredto, Gireve, and other PKI providers’ trust anchors will find their way into the EVs of various vehicle brands.

Note that the industry is moving toward Certificate Trust Lists (CTLs) – a simpler way to publish trusted Root CAs. The EU’s Sustainable Transport Forum (STF) is currently defining a PKI interoperability governance directive, which defines the guidelines for operating such a CTL. Current timelines hint at a publication by earliest 2026, more likely 2027.Remember that the corresponding private keys must also be stored for each leaf certificate, because they are needed to create the digital signatures: one for every contract certificate, potentially one for the OEM provisioning certificate (if contract certificate installation via the charging station is enabled), and one for the vehicle certificate (mutual authentication for ISO 15118-20 only).

Memory storage for chargers

In practice, most CPOs integrate with only a single PKI provider for issuing their SECC certificate chain. The dominant provider today is Hubject, whose V2G root CA is embedded in virtually all Plug & Charge-enabled EVs. As a result, ensuring regional interoperability seems to largely fall to vehicle OEMs, which must install all relevant V2G root CA trust anchors for the markets in which their vehicles are sold.

Building on the previous point, the CPO must install the V2G root CA trust anchor on the charger so that the charger can validate the SECC certificate chain during installation via OCPP.

To enable local validation of the contract certificate chain received from the EV during Plug & Charge authentication, the CPO must ensure that the trust anchors of all relevant MSPs are installed on the charger. While many MSPs are likely to rely on one of the existing V2G root CAs – like Digital Charging Services (DCS), used e.g. by BMW – some vehicle manufacturers who offer their own MSP service also operate a dedicated MSP root CA. Examples are Tesla, Rivian, Lucid, and Volkswagen (using Elli).

Finally, to support mutual authentication in ISO 15118-20 and verify the EV’s identity, the CPO must install all relevant trust anchors used by different vehicle brands. These trust anchors may be OEM-specific root CA certificates (if operated by the vehicle manufacturer, like Tesla, Rivian, Lucid, VW etc.) or V2G root CA certificates provided by a PKI provider – most commonly Hubject, which is currently the market leader.

The costs of maintaining SECC certificates

One note on the cost of issuing SECC certificates for CPOs: the price is about €0.99 per SECC certificate per year (Hubject’s price, may be similar with other PKI providers), effectively per charging station, as each charger typically has one ISO 15118 communication controller (the SECC, stands for Supply Equipment Communication Controller).

Although an SECC certificate must be renewed multiple times per year (typically three to four times), the fee is charged only once annually. As a result, the total cost of issuing and maintaining SECC certificates scales directly with the number of Plug & Charge-enabled charging stations deployed in the field.

Plug & Charge Direct – ISO 15118 & credit cards

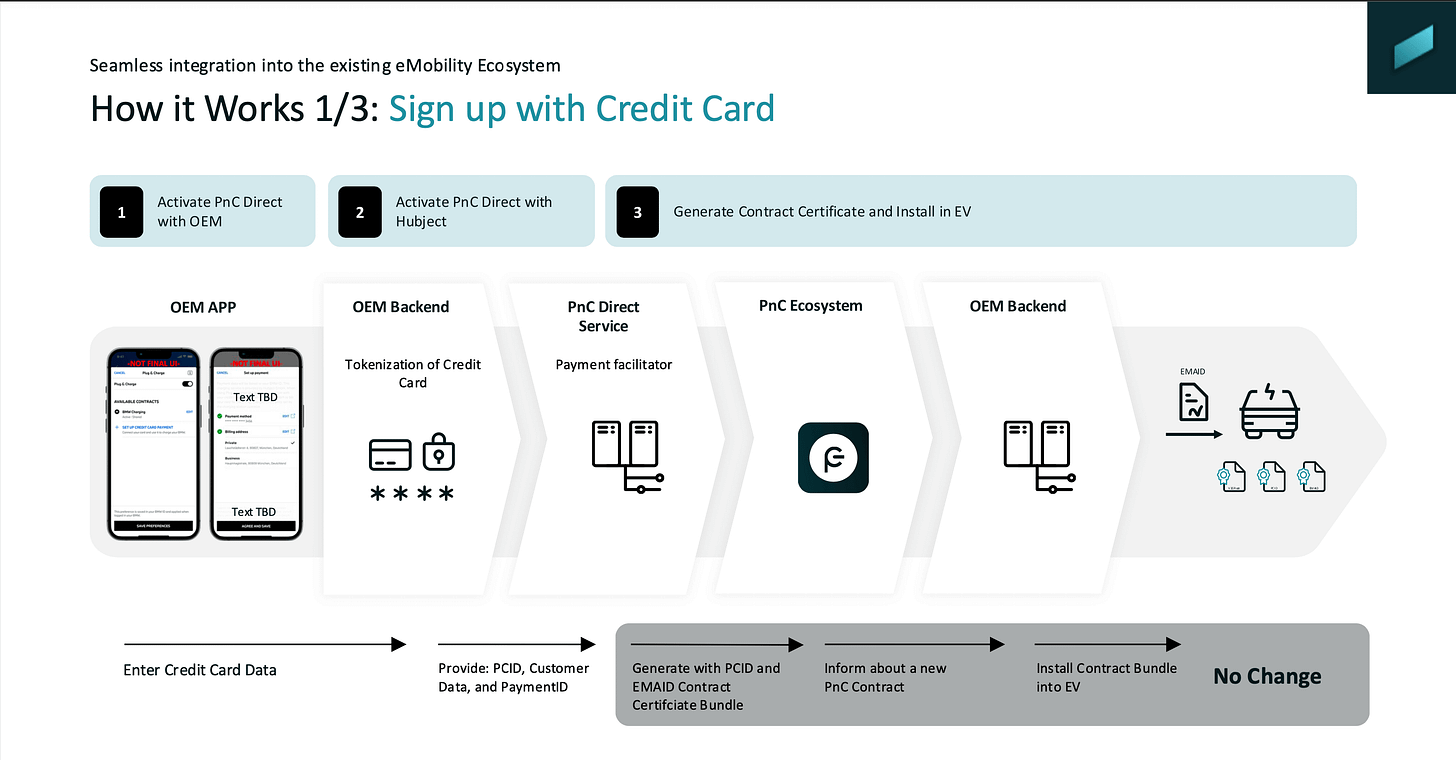

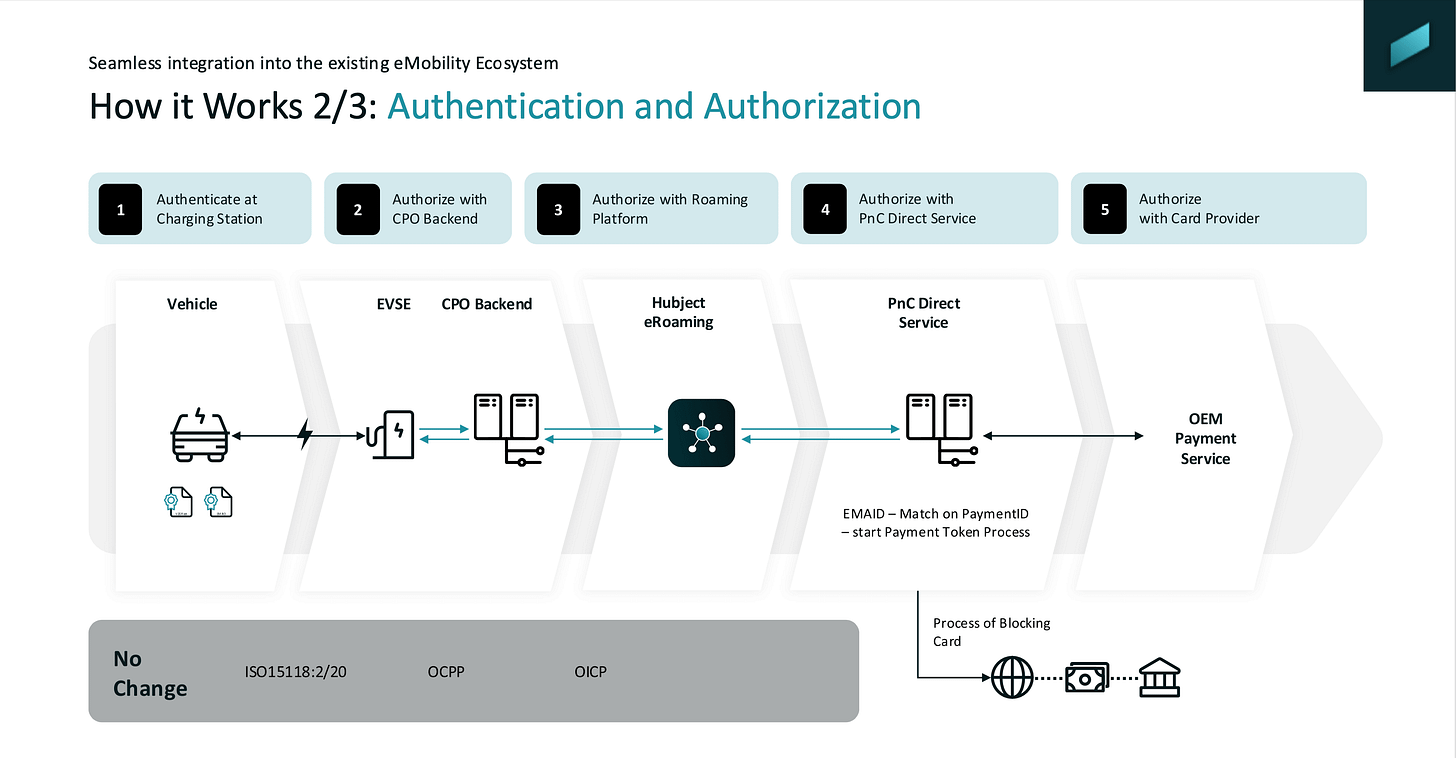

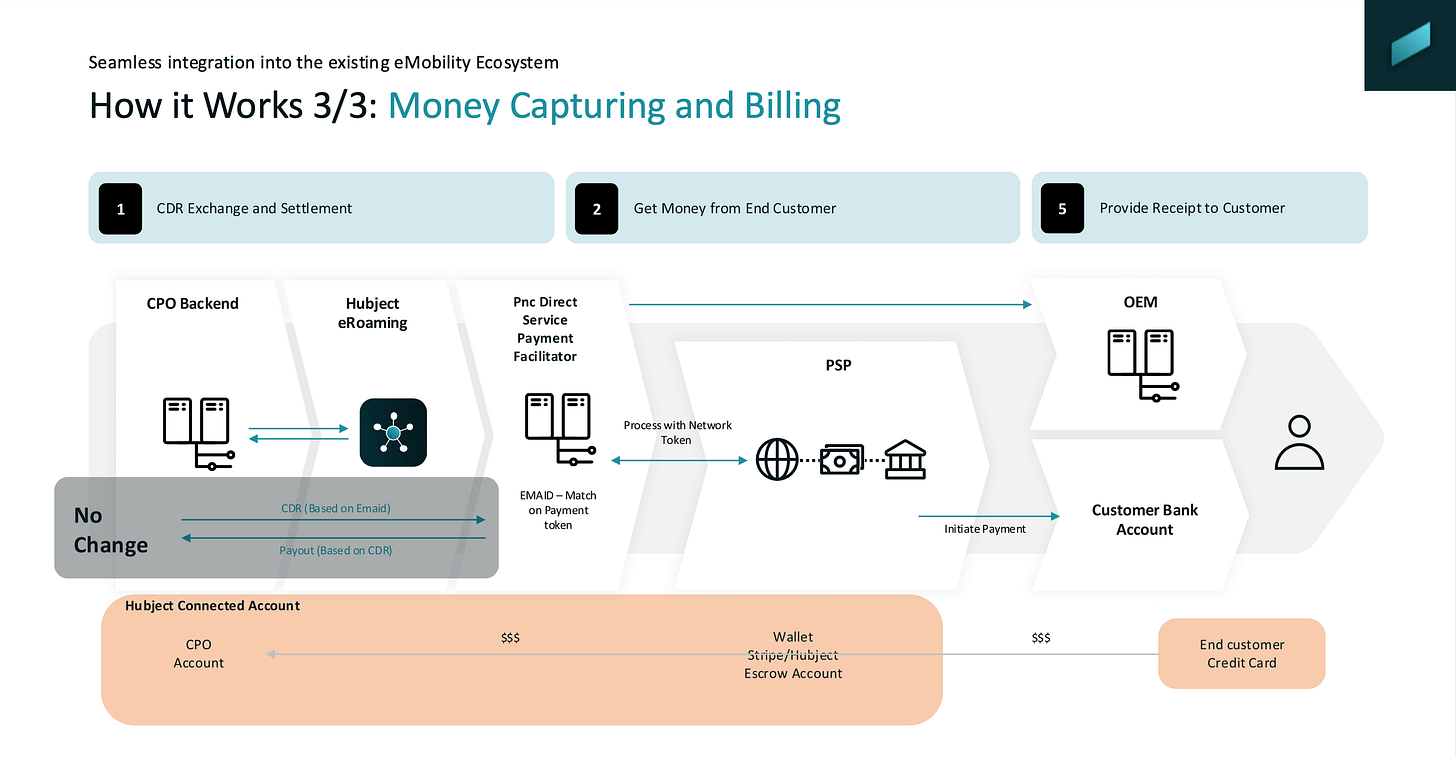

Before we close this chapter on Plug & Charge, I want to make you aware of a recent new development: Plug & Charge Direct.

Plug & Charge Direct was introduced by Hubject and fundamentally expands the classic contract-based Plug & Charge model by adding direct payment via credit card, without breaking the ISO 15118 flow. In short: drivers no longer need a pre-existing MSP contract. Instead, they can register a credit card once via the OEM app or vehicle HMI, after which charging works exactly like Plug & Charge today – just plug in and charge. Behind the scenes, a contract certificate is still generated and installed in the vehicle, but it is now linked to a payment token rather than an MSP account, preserving the familiar PKI-based authentication model.

What makes this interesting is how seamlessly it integrates into the existing ecosystem. The EV still authenticates via ISO 15118, the charger still talks OCPP to the CPO backend, and authorisation and clearing continue to flow through Hubject’s platform. The difference is that authorisation now also involves a Plug & Charge Direct service that matches the vehicle’s EMAID to a payment token and triggers credit-card-based settlement in parallel. For CPOs, this means broader access specifically to vehicle OEM fleet cars that may not be enabled for an MSP-based Plug & Charge experience. For drivers, it means Plug & Charge convenience, no contracts required, and full price transparency right in the car or app.

Mer and BMW were the first to implement this concept, let’s see how the market will evolve in this direction.

Thanks to Steffen Rhinow from Hubject for providing the slide deck, which explains this concept in more detail (see download link below).

And that’s a wrap for today.

If you’ve followed the full five-part Plug & Charge series – congratulations. You’re now pretty much an expert. You should have everything you need to be dangerous in the best possible way and to confidently support your team in bringing Plug & Charge products to market.

If you have any follow-up questions, feel free to drop them in the comments below or reply directly to this email (and don’t forget to sign up for the newsletter if you haven’t already).

I wish you a wonderful holiday break and some well-deserved days to recharge with friends and family. I’ll be taking a short break as well and will be back in January with a brand-new article series. Spoiler alert: we’ll dive into the exciting world of load balancing – and eventually vehicle-to-grid – analysed with the same level of detail and depth you’ve come to expect (and hopefully cherish) from this newsletter.

See you in 2026.